Table Of Contents

Recently I have spoken to many cloud-native organizations with strong platform engineering teams. I’ve seen a clear pattern across those platform teams. They build golden paths on Kubernetes, automate infrastructure, and streamline CI/CD. Developers get frictionless workflows for deploying apps.

But when I ask about databases, the mood changes.

“We don’t touch those — that’s the DBA’s job. There is another team managing Postgres.”

Or worse: “We just use RDS or Cloud SQL, but it doesn’t integrate with our platform. We only provide services for stateless apps.”

That gap is a big problem. If platform engineering is about enabling developers, the database can’t sit outside the platform. Databases are where code meets real-world data, where production mistakes surface, and where developer productivity often stalls. Leaving databases siloed undermines the entire mission of platform engineering.

The Evolution of the Platform Engineer Role

When platform engineering first emerged as a concept, the entire conversation revolved around Kubernetes. Engineers were tasked with building automation that made infrastructure consumption safe, repeatable, and developer-friendly. The focus was clear: design CI/CD pipelines, ensure reliable clusters, build secure and compliant environments. That work remains critical today.

But developer expectations have expanded. It is no longer enough to simply provide infrastructure on demand. Developers got spoiled with platforms such as Supabase. They want data on demand. They want to spin up staging databases that feel like production, roll back schema migrations without fear, and test new features against realistic datasets. They want workflows that include data from the start, not as an afterthought.

The reality, however, is that most internal platforms fall apart at the database layer. Everything looks polished until a team needs a database. Then the system reverts to a world of ticket queues, waiting for DBAs, or testing with mock datasets that fail to capture real production complexity. The shift is jarring: developers go from modern automation back to the way things were in 2008.

This gap slows releases, increases production risk, and undermines developer trust in the platform itself. For platform engineering to truly fulfill its promise, databases must move inside this golden path.

Why the database is the missing piece of platform engineering

Let me give a concrete example.

An ERP SaaS company I spoke with recently illustrates this problem clearly. They run a multi-tenant Postgres database for their customers, and their platform team managed the Kubernetes stack elegantly. On the surface, everything looked right: they had automated Kubernetes clusters, smooth CI/CD pipelines, and reliable service discovery. But when developers needed QA and staging environments, the story quickly unraveled.

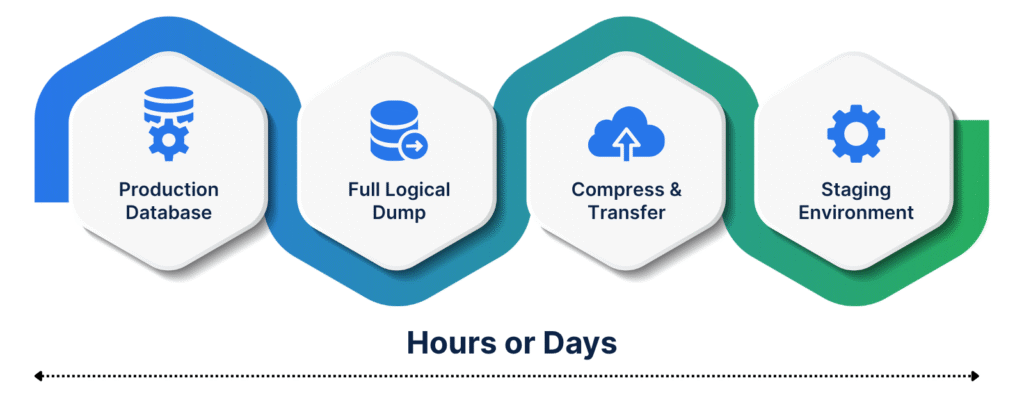

The team relied on traditional Postgres tools like pg_dump and pg_restore to create staging environments. This meant taking a full logical dump of the production database, compressing it, transferring it across environments, and then restoring it into a new Postgres instance. Even for a modest-sized database, the process consumed hours. For databases that had grown into hundreds of gigabytes or more, the process stretched into days. During that time, staging was either unavailable or hopelessly outdated, leaving developers to test against incomplete or mocked datasets.

Developers often pushed features that passed local testing but failed spectacularly when they hit staging or production. Subtle edge cases hidden in real customer data caused migrations to break. The feedback loop was painfully slow: wait days for a staging refresh, run tests, discover an issue, fix it, then repeat the cycle. What looked like a polished golden path from the infrastructure perspective collapsed completely at the database layer.

The result was predictable. Features slowed down. Customers got frustrated. Rollbacks became more common. Production confidence eroded. The platform team had built a beautiful developer experience — except it stopped short of the database. And without the database in the loop, the golden path wasn’t golden at all.

Owning the database experience doesn’t mean platform engineers replace DBAs. It means recognizing that developers need more than bare infrastructure. If they can spin up ephemeral Kubernetes clusters in seconds, they should also be able to spin up ephemeral Postgres databases in seconds. Without that ability, the platform remains incomplete, and the developer experience is compromised from the start.

The Kubernetes operator trap

Some teams recognize this gap and try to solve it by adopting Kubernetes operators like CloudNativePG. On paper, this looks promising. Postgres can be deployed inside Kubernetes, aligned with existing workflows, and automated like other workloads.

But in practice, the story is rarely so clean. Suddenly, platform engineer’s role is not just being Kubernetes expert; they are expected to become Postgres experts too. Backups, failover, replication, monitoring, and tuning land on their shoulders. Schema migrations, drift detection, and rollback strategies become their problems. Instead of reducing complexity, this approach shifts operational burden from DBAs to platform engineers.

And then, after all this effort, the teams end up with nothing more than a plain Postgres database. There is no built-in developer workflow, no branching, no automatic refresh, no compliance guardrails. It is simply a static environment that begins drifting from production the moment it is created. Developers still file tickets for migrations. DBAs still spend hours firefighting. And platform engineers are left managing a brittle process that doesn’t scale.

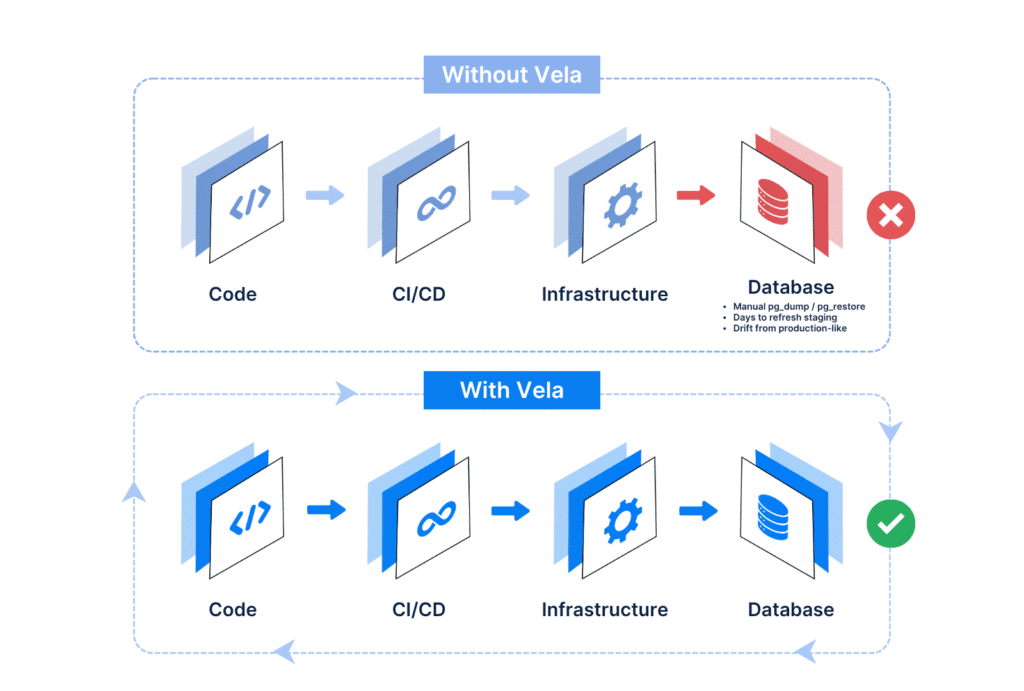

By contrast, with Vela the experience is entirely different. Instead of delivering a raw database that developers have to work around, platform teams deliver a Postgres BaaS experience inside their own cloud. Developers can spin up instant clones, branch databases like Git, roll back with time travel, and integrate data environments directly into CI/CD. Compliance is handled with IAM, RBAC, and audit logs. Staging never drifts from production because every environment is cloned in seconds from the real dataset.

Without Vela, platform engineers not only spend countless hours on manual operations, they also carry the operational burden of Postgres itself. Backups, failover, replication, monitoring, and tuning suddenly fall on their shoulders. Every schema migration, drift detection issue, and rollback strategy becomes their problem. Instead of reducing complexity, this approach simply shifts it.

Platform teams already carry enormous responsibility. They are expected to make developers’ lives easier, not harder. Asking them to become experts in Postgres internals only adds weight. It’s the wrong direction for a role that is meant to simplify, abstract, and standardize.

Why I believe Vela changes the equation

This is where Vela comes in. Vela was designed precisely because we saw how painful “DIY database management” had become for platform teams. At its core, Vela is not just another hosted Postgres instance. It is a Postgres Data Platform — a true backend-as-a-service that runs inside your own cloud. Instead of delivering a plain database that requires endless operational work, Vela provides a complete developer experience with instant cloning, branching, compliance, and orchestration built in.

With Vela, staging and QA environments no longer take days of manual effort with pg_dump and pg_restore. A terabyte-scale Postgres database can be cloned in less than a second. Developers can branch, test, and merge database changes just like they do with code. Compliance is handled through built-in enterprise features such as RBAC, IAM integration, and audit logs. And because Vela runs in your own cloud, you retain full control over cost, performance, and data residency.

The key advantage is simplicity. Platform engineers do not need deep Postgres expertise to deliver a production-grade experience. They no longer spend weeks building fragile operators or wrestling with backups, failover, and monitoring. Instead, they provide developers with self-service databases as easily as they provide Kubernetes clusters. DBAs stop firefighting, platform engineers stop reinventing Postgres, and developers finally gain the speed and confidence they need to ship software without bottlenecks.

Addressing the compliance angle

The moment I describe developer self-service databases, I often hear a serious objection: “What about compliance? Our data is sensitive. We can’t just give developers free rein.”

This is a valid concern. Databases contain sensitive customer data, and compliance requirements are non-negotiable. But this is not an argument against database self-service; it is an argument for platform ownership. Platform teams already own compliance guardrails for infrastructure. The same responsibility should apply to databases.

With Vela, compliance isn’t an afterthought. Clones can be anonymized automatically. IAM ensures that developers only access the data they are allowed to see. Since Vela runs in your own cloud, data residency and regulatory requirements like GDPR or HIPAA are met by design. Security is not compromised; it is strengthened by making compliance workflows part of the golden path.

The business impact of platform-owned databases

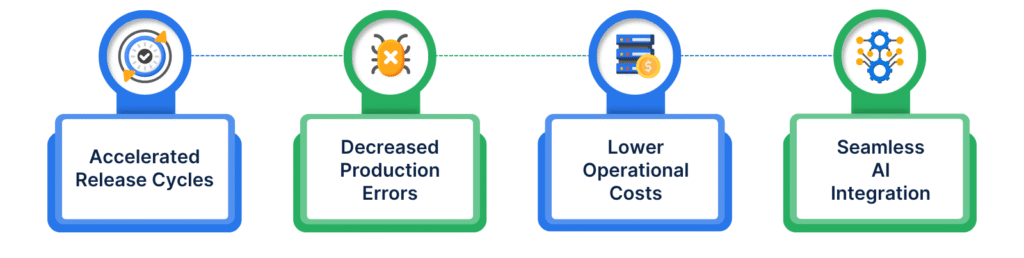

This debate is not just technical. The business impact of platform-owned databases is tangible. Release cycles accelerate when developers test against production-like data earlier in the process. Production errors decrease because schema migrations and rollbacks are validated in safe environments before going live. Costs drop because thin clones replace full-size environments.

Beyond these benefits, owning the database experience unlocks entirely new opportunities. Postgres is no longer just a transactional database. With vector search, time-series support, and analytics capabilities, it doubles as an AI backend. This means faster adoption of machine learning and AI-driven features, without needing to manage separate data platforms.

When the database becomes part of the platform, it stops being a bottleneck and starts being a competitive advantage.

Platform Engineers won’t turn into DBAs

Owning the database experience does not mean platform engineers must become DBAs. It means they recognize that delivering a complete developer experience requires extending the golden path all the way through the data layer. Developers expect infrastructure and data to be equally accessible.

The choice is clear. Teams can continue bolting on Kubernetes operators and absorbing the operational burden, or they can adopt an integrated Postgres data platform that abstracts complexity away. Vela makes databases as easy to manage as the rest of the stack, without giving up control, compliance, or performance.

The future of platform engineering includes databases by default. With Vela, that future is already available.

👉 If you’re curious how this works in practice, try the Vela Demo or check out the cost calculator to see what owning the database experience could mean for your team.