Storage Fault Domains vs Availability Zones

Terms related to simplyblock

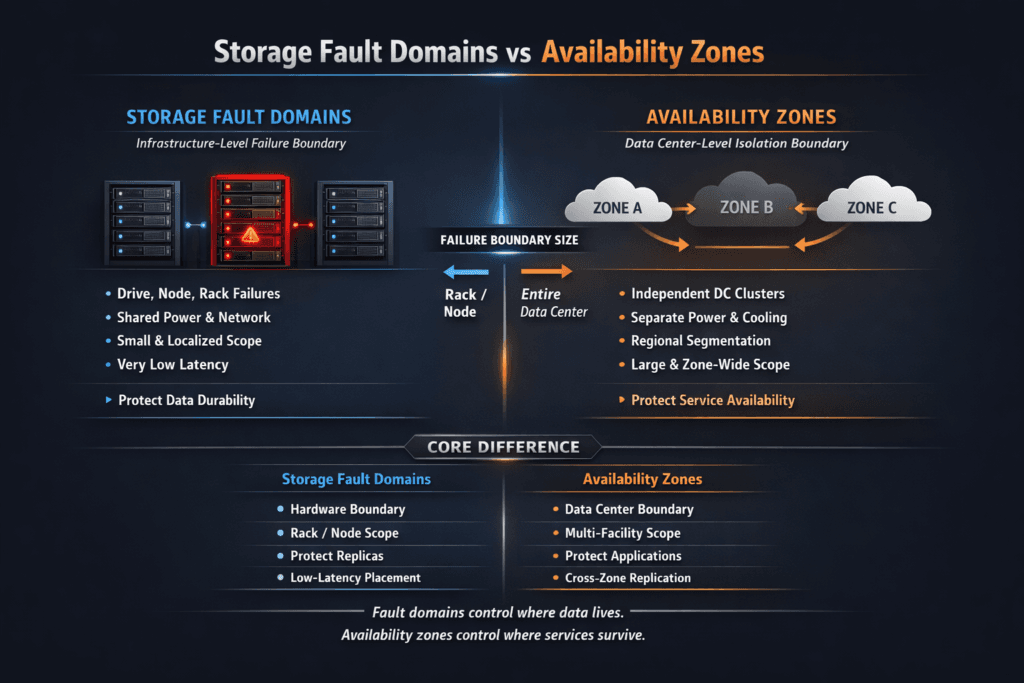

Storage Fault Domains vs Availability Zones describes two ways to define “what can fail together,” and how that choice shapes data safety, uptime, and cost. A fault domain groups components that share a single risk, such as a rack, a top-of-rack switch, a power feed, or a storage node set. An availability zone (AZ) is a larger boundary that cloud providers design to limit shared-risk events across separate locations inside a region.

For Kubernetes Storage, this difference matters because placement rules drive how your platform spreads replicas, erasure-coded stripes, and quorum members. If you pick the wrong boundary, you either waste resources or accept more risk than you think. In practice, platform teams want a clear answer to one question: “What failure do we survive without losing data or availability?”

Planning resilience boundaries for modern platforms

Teams get better results when they define boundaries in plain terms, then map policies to those boundaries. Start with the failures you must survive: a node loss, a rack outage, or a whole zone outage. Then match the storage policy to that scope.

A fault-domain-first model fits many on-prem and bare-metal fleets because you control the physical layout. You can spread replicas across racks, power domains, or rows. An AZ-first model fits public cloud because the cloud provider exposes zone labels that work well with scheduling and placement.

Either way, Software-defined Block Storage helps because it can encode policy at the volume level. QoS also keeps tenant behavior under control, so a busy namespace does not drag rebuild time into your core services.

🚀 Cut Cross-Zone Cost While Keeping Storage Resilient

Use simplyblock to set tiered durability policies across racks and zones, per volume.

👉 Use simplyblock multi-tenancy and QoS →

Storage Fault Domains vs Availability Zones in Kubernetes Storage Scheduling

Kubernetes uses labels and topology rules to place workloads and, with CSI, to place volumes. When your nodes carry consistent zone labels, Kubernetes can spread pods across zones and keep volume placement close to the pod. When your storage layer understands a smaller fault domain, such as a rack boundary, it can place replicas across racks even inside the same zone.

Alignment matters more than any single feature. If your workload spreads across zones, but your storage replicates only inside a rack, you can lose data during a zone event. If your storage replicates across zones, but your workload stays in one zone, you pay extra write cost without a real uptime gain.

A strong platform standardizes labels, StorageClass intent, and replica placement rules. That standard reduces risk during node drains, upgrades, and autoscaling.

Storage Fault Domains vs Availability Zones with NVMe/TCP fabrics

NVMe/TCP makes shared storage feel closer to local NVMe because it carries NVMe commands over standard Ethernet. For multi-zone or multi-rack designs, NVMe/TCP keeps the network model simple, which helps operators scale without special fabrics.

The boundary choice still drives performance. Cross-zone replication adds latency and network cost, so it can raise write tail latency for strict durability modes. Rack-level replication often keeps latency lower, but it cannot cover a full zone event. Many teams run a tiered model: protect most volumes across fault domains in the same zone, then reserve cross-zone durability for the services that need it.

This is where Kubernetes Storage policy meets transport choice. NVMe/TCP can carry the traffic, but the StorageClass policy decides how far the data travels, how fast it acknowledges writes, and how rebuild behaves during churn.

Measuring Storage Fault Domains vs Availability Zones’ impact on performance

Measure what users feel: p95 and p99 latency, not only average IOPS. Then measure what operators feel: rebuild time and recovery time during failures. A boundary decision changes both.

A practical test plan includes a steady load plus a disruption. Run a baseline with normal replica count. Next, drain a node and watch attach and mount time, plus tail latency. Then simulate a rack or zone event and measure recovery time, resync traffic, and how quickly the platform returns to steady performance.

If your data path looks fast but recovery takes too long, the boundary and policy do not match your SLO. If recovery looks great but write latency jumps under load, you likely pushed durability too far for that tier.

Operational approaches to balance durability and cost

Most teams improve outcomes by making boundaries explicit, then tying each workload tier to a clear policy:

- Define fault domains for on-prem fleets, such as rack, power feed, and storage node set.

- Use zone labels consistently across clusters, so scheduling and volume placement match.

- Choose replication scope per tier, and avoid cross-zone writes for workloads that do not need them.

- Set QoS limits to protect rebuild and resync from noisy neighbors.

- Validate recovery behavior during node drains, rack events, and zone events.

Side-by-side comparison of failure boundaries

The table below summarizes how these boundaries differ in scope, typical use, and common trade-offs.

| Boundary | What it usually represents | Primary strength | Common trade-off |

|---|---|---|---|

| Storage fault domain | Rack, power, switch, or storage node group | Fine-grained control and efficient replication | Does not cover a full zone outage |

| Availability zone | Provider-defined isolated location in a region | Strong protection from site-level issues | Higher latency and cost for cross-zone writes |

| Region | Large geographic boundary | Disaster recovery scope | Much higher latency and higher complexity |

| Node | Single machine | Fast local behavior | Lowest resilience without replicas |

Policy controls for steady outcomes with simplyblock™

Simplyblock™ fits this problem because it treats failure boundaries as part of the storage policy, not as tribal knowledge. Platform teams can set rules that place replicas or erasure-coded data across the right boundaries, then apply those rules through StorageClasses.

This approach pairs well with NVMe/TCP because it supports shared storage on Ethernet while keeping operations familiar. In multi-tenant clusters, QoS and tenant controls help protect critical services during resync and rebuild. When the platform controls rebuild pressure, teams spend less time in degraded states, which lowers risk.

Simplyblock also targets efficient I/O paths with an SPDK-based, user-space design, which helps when the platform runs high concurrency and still needs stable tail latency.

Where topology-aware storage design is headed

Teams will keep pushing toward clearer, policy-driven placement across fleets. Expect tighter links between scheduling, topology rules, and volume policy, so workloads land in the right place without manual steps. Expect more use of automated risk profiles, where a StorageClass encodes both “how far data spreads” and “what latency budget it must meet.”

As NVMe devices get faster, the platform will also care more about CPU cost per I/O. That trend favors lean data paths, smart QoS, and transport choices like NVMe/TCP that scale across common networks.

Related Terms

Teams often pair Storage Fault Domains vs Availability Zones with these pages when they set topology and durability rules.

- Region vs Availability Zone

- CSI Topology Awareness

- Cross-Zone Replication

- Kubernetes Topology Constraints

Questions and Answers

An availability zone is a cloud-defined boundary, but a storage fault domain is the actual blast radius your data placement assumes, like a node, rack, ToR switch, power feed, or even a shared storage controller. If you treat AZs as the only domain, you can still lose multiple replicas to a single correlated event inside one AZ. Map placement to true boundaries, not just regions vs availability zones.

Multi-AZ helps only if replicas or shards are forced into distinct domains, and your control plane also survives. If your storage layer concentrates primaries in one AZ, or metadata/quorum members share hidden dependencies, an AZ-local incident can still cause unavailability or unsafe recovery. Validate that durability assumptions match your fault tolerance design, not just your cloud topology labels.

Erasure coding is only as strong as the shard distribution. If multiple shards land in the same fault domain (same rack or ToR), you can lose “N+2” protection during a single localized outage, even within one AZ. The fix is strict domain-aware placement rules that align shards with independent failure boundaries. This is the practical side of erasure coding beyond the math.

Spreading across AZs reduces correlated failure risk, but it often increases latency and jitter because reads/writes traverse inter-AZ networks. Keeping copies within smaller domains (rack-level) can be faster but weaker against larger outages. Many systems mix both: fast local replicas plus remote copies for disaster recovery. Your optimal balance depends on the distributed block storage architecture and its rebuild/degraded-mode behavior.

Don’t rely on “AZ diversity” dashboards alone. Check where primaries, replicas, and quorum/metadata services land, and confirm placement rules enforce separation across your intended domains. Early warning signs show up as skewed replica distribution, hotspot nodes, and rebuild storms after small failures. Track scheduling and backend signals with storage metrics in Kubernetes to catch domain imbalance before it becomes an incident.