Failure Domains in Distributed Storage

Terms related to simplyblock

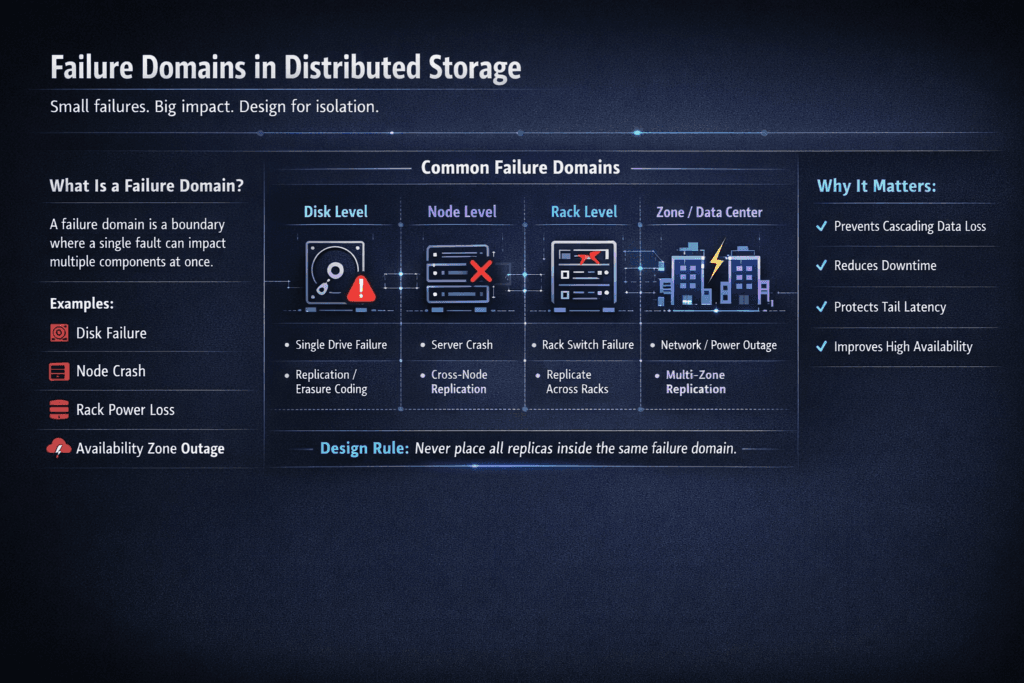

Failure domains in distributed storage describe the parts of a storage system that can fail together. A failure domain can be a drive, a node, a rack, a zone, or an entire region. When teams plan for the wrong domain, they risk data loss, long rebuilds, or a wide service hit.

Distributed systems spread data across many parts, but they also introduce shared risks. Power feeds, top-of-rack switches, and zone events can take out multiple nodes at once. Strong designs map data placement and recovery behavior to real infrastructure boundaries, not just to server count.

This topic matters most when you run Kubernetes Storage for databases, queues, and analytics. Those workloads punish tail latency, and they surface rebuild pain fast. Software-defined Block Storage helps when it enforces placement rules and QoS so a failure event does not turn into a platform-wide slowdown.

Failure Domains in Distributed Storage – What Breaks Together

A failure domain is a practical boundary for related loss. If two components share the same power, network path, or control plane, treat them as one risk.

In distributed storage, the common domains include drives, nodes, racks, zones, and regions. Each step up increases the number of systems affected in one event. Each step up also changes the recovery plan, from a simple rebuild to a full failover.

Teams often overlook network and control plane risks. A cluster can keep data safe and still stall apps if traffic cannot route around a switch failure or a rebuild wave floods the fabric.

🚀 Run Distributed Block Storage With Clear Failure Boundaries

Use Simplyblock to scale out storage while keeping rebuild impact under control with QoS.

👉 See Distributed Block Storage Architecture →

Kubernetes Scheduling Meets Storage Boundaries

Kubernetes Storage adds scheduling rules, reschedules, and volume lifecycles. Your failure-domain model must match how Kubernetes places Pods and volumes.

If a workload runs across zones, the platform must place replicas across zones, too. If it keeps primary and replica in the same zone, a zone outage can take both down. If it spreads replicas correctly but provisions volumes in the wrong place, it pays with latency spikes and slow recovery.

Good designs align three layers. The scheduler spreads Pods across the right boundaries. The CSI layer provisions volumes in those same boundaries. The storage layer places data replicas so that one event does not remove all copies.

When these layers line up, Kubernetes Storage stays stable during drains and failures. When they fight, the cluster burns time on reattach work, cross-zone traffic, and p99 latency spikes.

Failure Domains in Distributed Storage on NVMe/TCP Fabrics

NVMe/TCP offers NVMe-oF transport over standard Ethernet, which fits many data centers and clouds. It also enables disaggregated designs where compute nodes access remote NVMe-backed volumes without a legacy SAN stack.

The failure-domain story changes with fabrics. A local NVMe device mostly sits inside the node domain. A remote NVMe/TCP target adds switches, links, and routing paths that can fail together. That does not make the design weaker, but it does require clear multipath behavior, redundant links, and placement rules that avoid putting all replicas behind one shared choke point.

CPU cost matters, too. SPDK-style user-space data paths reduce overhead and help keep service steady during spikes. That matters most during rebuilds, when the system must move a lot of data while still serving foreground I/O.

Failure Domains in Distributed Storage Under Load Testing

Failure testing should answer one question: what happens to latency and recovery time when something breaks?

Start with steady-state performance, then introduce failure events while the load stays on. Measure p50, p95, and p99 latency, track throughput, and record rebuild time. Watch the impact of rebuild traffic on foreground traffic, because fast healing can still crush application latency.

Run a focused set of tests that cover the domains you care about: drive loss, node drain, rack loss simulation, and zone loss simulation in staging. Repeat with a multi-tenant load so you can see whether QoS keeps critical workloads stable.

Testing without load hides the real cost. Testing with only one workload also hides noisy-neighbor effects.

Practical Controls That Reduce Blast Radius

The most useful controls reduce related loss and keep rebuilds from starving production I/O. Map replicas to real boundaries like nodes, racks, and zones. Reserve I/O budget for foreground traffic so rebuild work does not throttle apps.

Apply QoS per tenant and per volume so one team cannot flood the cluster. Use multipath and redundant links for NVMe/TCP fabrics, and validate failover behavior. Set recovery targets for each domain, then test them with a production-like load.

Failure-Domain Trade-Offs for Distributed Block Storage

A simple comparison helps clarify which domain you should target for each workload tier. Smaller domains recover faster. Larger domains protect against bigger events, but they add cost and coordination work.

| Failure domain target | What it protects against | Typical cost | Common fit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Node | Host loss, local SSD loss | Low | Dev/test, edge, smaller tiers |

| Rack | Shared power or ToR failure | Medium | Shared clusters, core services |

| Zone | AZ or zone outage | Higher | Regulated apps, HA tiers |

| Region | Region-wide outage | Highest | DR, strict business apps |

Policy-Driven Resilience with simplyblock™

Simplyblock™ supports Kubernetes Storage with an NVMe/TCP data plane and a Software-defined Block Storage control model. That combination helps teams enforce placement and isolation across node, rack, and zone boundaries.

For platform owners, the value comes from three areas. First, the system can apply policy, so replicas do not land in the same shared-risk boundary. Second, QoS and multi-tenancy reduce the chance that rebuilding work or one noisy tenant drags down every service. Third, the SPDK-based approach targets lower overhead in the hot path, which helps keep CPU headroom for applications during bursts and failures.

What Changes Next for Resilience, DPUs, and Multi-Cluster DR

Teams want smaller, clearer failure domains, and they want faster recovery. That pushes designs toward better topology signals, smarter placement, and stricter isolation for shared clusters. It also pushes platforms to measure and manage tail latency, not just peak IOPS.

DPUs and IPUs will matter more as storage traffic grows. They can take on parts of the data path, which frees CPU for apps and helps reduce jitter under load. Multi-cluster designs will also become more common, especially where a region-level event drives real business risk.

Related Terms

These glossary pages support Kubernetes Storage, NVMe/TCP, and Software-defined Block Storage decisions.

- Pod Topology Spread Constraints

- CSI Topology Awareness

- Zonal vs Regional Storage

- High Availability Block Storage Design

Questions and Answers

A failure domain is the largest component set you assume can fail together, like a node, rack, or availability zone. Once you pick it, replication or erasure-coding placement must ensure fragments land in different domains, not just different disks. If your “domain” is too small, correlated outages can wipe multiple copies at once. Align it with real infrastructure boundaries like regions vs availability zones.

For N+2, you need at least three distinct failure domains if you want to survive a full domain loss without data unavailability. If fragments cluster because you only have two domains, a single domain outage can remove too many shards and turn a “durable” scheme into an availability incident. This is why erasure coding must be paired with strict placement rules.

Replication is a simpler operationally because any intact copy can serve reads immediately after a failure, but it costs more raw capacity. Erasure coding is capacity-efficient, yet rebuild and degraded-mode reads can amplify latency if the system must pull shards across domains. The right choice depends on your SLA and recovery behavior in your distributed block storage architecture.

Even if data shards are well distributed, control-plane services (metadata, monitors, consensus groups) can become the real limiting failure domain. If quorum members share a rack, top-of-rack switch, or power feed, a single event can stall the whole cluster despite intact data. Model these dependencies explicitly and validate them against your fault tolerance assumptions.

Look for skew: one zone carrying more primaries, hotter shards, or more rebuild work than others. Early signals show up as tail-latency drift and background-rebuild contention, not average throughput drops. Track placement distribution and watch p95/p99 plus rebuild bandwidth using storage metrics in Kubernetes so you can rebalance proactively.