Kubernetes AccessModes vs VolumeModes

Terms related to simplyblock

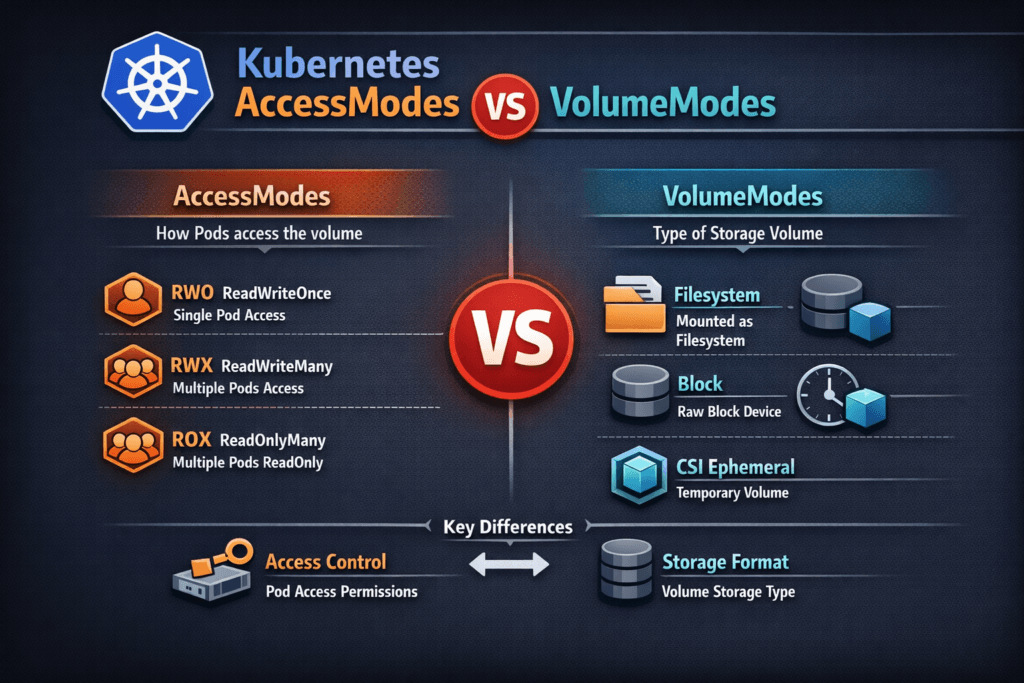

Kubernetes AccessModes vs VolumeModes compares two PVC settings that solve different problems. AccessModes define who can mount a PersistentVolume and how, such as ReadWriteOnce (RWO), ReadOnlyMany (ROX), ReadWriteMany (RWX), and ReadWriteOncePod (RWOP). VolumeModes define how Kubernetes presents the volume inside the pod, either as a Filesystem mount or as a raw Block device. Kubernetes defaults volumeMode to Filesystem when you omit it.

Teams confuse these fields because both appear on the same claim. The cluster enforces AccessModes at attach and mount time, while volumeMode shapes the data path the app sees. When you match both to the workload, you reduce mount errors, avoid surprise reschedules, and keep performance steady in Kubernetes Storage.

Policy design for safer mode choices in production

AccessModes drive placement and scale behavior. RWO lets multiple pods mount the same volume only when they run on the same node, so it pairs well with StatefulSets and strict scheduling. RWX enables multi-node mounts, which helps shared content, but it can raise coordination needs and latency risk, depending on the backend. RWOP tightens safety further by limiting the volume to one pod in the cluster.

VolumeModes drive app expectations. Filesystem mode fits most apps because it provides directories, permissions, and common tools. Block mode fits apps that manage their own data layout, or tools that prefer raw devices. If you choose Block, the pod consumes the device path directly, and your app owns partitioning and formatting decisions. OpenShift and Kubernetes APIs document this behavior in the PVC schema.

🚀 Standardize AccessModes and VolumeModes for Stateful Apps on NVMe/TCP

Use Simplyblock to deliver Software-defined Block Storage with consistent PVC behavior in Kubernetes Storage.

👉 Use Simplyblock for Kubernetes Storage →

Kubernetes AccessModes vs VolumeModes in Kubernetes Storage

In Kubernetes Storage, the PVC binds to a PV, and the CSI driver handles provisioning and node-side publish steps. AccessModes tell the control plane what mount patterns you intend. volumeMode tells the node whether it should mount a filesystem or map a raw device into the pod.

A common example: a database uses RWO with the filesystem to get simple operations and fast recovery. Another example: a performance-sensitive engine uses RWO with Block so it can skip filesystem work and manage I/O at the device layer. Both examples can work, but they require the right StorageClass behavior, node permissions, and backup plan.

Kubernetes AccessModes vs VolumeModes and NVMe/TCP

NVMe/TCP matters here because it changes the cost of remote I/O. When you run Software-defined Block Storage over NVMe/TCP, you can deliver low overhead on standard Ethernet while keeping the Kubernetes experience consistent.

VolumeModes influence how much work happens above the device. Filesystem mode adds filesystem metadata and caching behavior, which many apps like. Block mode can reduce overhead for certain patterns, especially when the app already controls layout and sync rules. NVMe/TCP helps both modes by cutting protocol overhead compared to older network storage patterns, and it supports scale-out designs that fit Kubernetes Storage lifecycles.

Benchmarking the mode choice for latency and throughput

Benchmarking should compare the same workload under two PVC specs: Filesystem vs Block, with the same AccessMode, size, and node placement rules. Measure average latency, p95 and p99 latency, and throughput under read-heavy, write-heavy, and mixed tests. Then rerun the test during node drains and rolling updates to see how the system behaves when Kubernetes reschedules pods.

Tie the results to node signals. CPU saturation, network drops, and storage queue depth often explain “mode” issues that look like storage problems. A clear benchmark plan keeps platform teams from tuning the wrong layer.

Common misconfigurations that break apps

Mode issues usually show up as mount failures, stuck pods, or poor tail latency. If you request RWX on a backend that cannot serve it, Kubernetes may fail the claim, or the driver may reject the attach. If you request Block but your app expects a mounted path, the container will start without the directory structure it needs. If you set RWO and then scale a Deployment across nodes, Kubernetes will fight your intent, and you will see scheduling churn. The Kubernetes PV docs call out the meaning of AccessModes, and OpenShift’s PVC API doc clarifies volumeMode behavior.

Kubernetes AccessModes vs VolumeModes comparison table

This table highlights how the two settings differ, and how they affect design and operations.

| Item | What it controls | Common values | What it changes in practice |

|---|---|---|---|

| AccessModes | Who can mount the PV | RWO, ROX, RWX, RWOP | Scheduling flexibility, multi-attach rules, scale patterns |

| VolumeModes | How the pod consumes storage | Filesystem, Block | Path vs device access, formatting responsibility, I/O stack shape |

Simplyblock™ pattern for stable AccessModes and VolumeModes

Simplyblock™ focuses on Software-defined Block Storage that fits Kubernetes Storage primitives and high-performance stateful workloads. It provides NVMe/TCP-based volumes through CSI, which helps teams keep volume operations consistent during scale events and upgrades.

Simplyblock™ also builds on SPDK-style user-space acceleration to reduce kernel overhead and improve CPU efficiency, which helps when you run many stateful services on bare metal or mixed clusters. This approach supports clean separation between control plane policy (AccessModes) and the data path choice (Filesystem or Block), without forcing application rewrites.

Where Kubernetes mode handling is heading next

Kubernetes keeps adding clearer controls around placement, attachment, and workload safety. RWOP already tightened semantics for single-pod writers, and more teams now treat these fields as policy, not app-by-app tuning.

On the infrastructure side, faster networks and user-space I/O stacks will keep pushing down latency variance. NVMe/TCP, DPUs, and better CSI metrics will make it easier to see whether the bottleneck sits in the node, the network, or the storage backend.

Related Terms

Teams often review these glossary pages alongside Kubernetes AccessModes vs VolumeModes when they standardize Kubernetes Storage and Software-defined Block Storage.

- AccessModes in Kubernetes Storage

- CSI NodePublishVolume Lifecycle

- Kubernetes Volume Attachment

- Kubernetes StorageClass Parameters

- Kubernetes Volume Mode (Filesystem vs Block)

Questions and Answers

AccessModes define how many pods can access a volume (e.g., ReadWriteOnce, ReadOnlyMany), while VolumeModes determine how the volume is presented (e.g., Filesystem vs Block). Choosing the right combination is critical for Kubernetes Stateful workloads.

Most CSI drivers support ReadWriteOnce, with growing support for ReadWriteOncePod and ReadWriteMany. Simplyblock’s Kubernetes CSI driver is compatible with the most common access patterns in production environments.

Use Block When the application needs raw disk access without a filesystem—common for databases or performance-tuned storage engines like PostgreSQL on Simplyblock. Use Filesystem for general-purpose apps.

No. Not all combinations are supported. For example, ReadWriteMany is rarely compatible with Block the mode. When designing persistent storage using block storage replacement, validate compatibility with your CSI driver.

AccessModes define sharing policies, while VolumeModes impact data layout. For security-sensitive workloads, pairing ReadWriteOnce with encryption at rest ensures isolated, secure, and compliant storage usage.